“We must forget ourselves and work for others, even if what we do today may or may not bear fruit until two or three generations.”

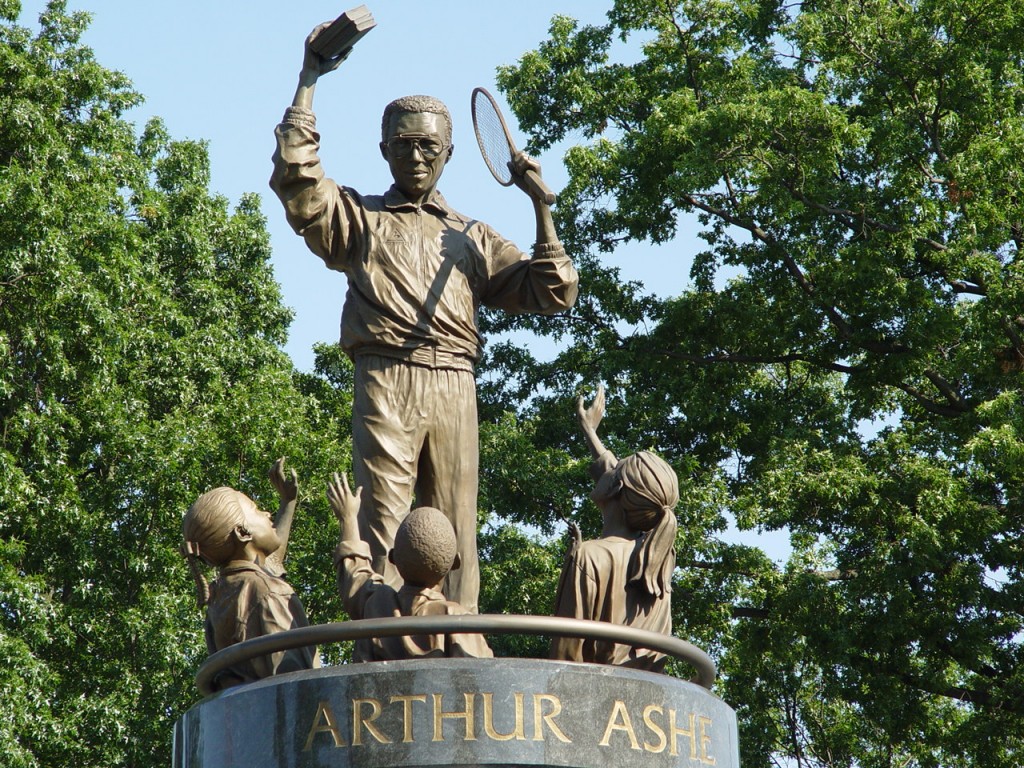

When ESPN counted down the top 100 athletes of the 20th century, eight tennis players made the list. Yet the name of Arthur Ashe, who won several tennis championships in the 1960s and 1970s, was nowhere to be found. This was not necessarily an error in judgment or an oversight by the selection committee. Arthur was undoubtedly considered for the list, but the athletes were judged solely on their on-court performances, not what they did off the court. If the selection criteria had included character and off-the-court accomplishments, the outcome would have been far different. As ESPN commentator Dick Schaap put it, “Arthur Ashe was a very, very, very good tennis player, but he was not one of the two or three greatest tennis players of all time. But if you voted on the two or three most impressive, most significant athletes of all time, you would put Arthur Ashe up there with Jackie Robinson and Muhammad Ali.” Arthur was indeed a great tennis player—at one point in his career he was ranked #1 in the world—but he was unquestionably a better person than he was an athlete.

In 1993 ESPN, the same organization that did not include Arthur in its list of the century’s top 100 athletes, created the ESPY Awards to recognize top achievements in sports. The most prestigious part of this event is an award that is presented annually to an individual whose contributions transcend sports. This award is appropriately named the Arthur Ashe Courage Award to commemorate Arthur’s role as a humanitarian and a champion of important causes. The first person to win this esteemed award was Jim Valvano, the famed former basketball coach at North Carolina State University, who was dying of cancer at the time. Other notable winners of the award include Muhammad Ali (1997), Pat Tillman (2003), Ed Thomas (2010) and Pat Summitt (2012). These individuals and the other recipients are recognized as heroes and role models. Yet the award is named for a quiet, skinny tennis player who is generally not ranked among the world’s best athletes. Why did ESPN believe Arthur Ashe should be the one person so closely associated with this award? What did he do to set himself apart from all the other athletes who came before him?

To properly answer this question, one must start at the beginning. Arthur was born in 1943 and was raised in Richmond, Virginia. Arthur’s home state of Virginia, like most Southern states at the time, was racially segregated. As a black child, Arthur was not allowed to go to school with or play tennis with white children. He knew that applying to the leading university in his home state, the University of Virginia, was a waste of his time because it was segregated—for whites only. Segregation was legally sanctioned and permeated every aspect of daily life. Blacks and whites could not eat together in restaurants, ride together on the bus, or use the same water fountains or bathrooms. Despite not being able to play in youth tournaments, Arthur’s game progressed quickly and he was awarded a tennis scholarship to the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). While playing tennis at UCLA, Arthur won the NCAA singles championship and led his team to the national championship in 1965.

It is fair to say that Arthur was the Jackie Robinson of tennis. As most people know, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball and went on to be one of the finest athletes to ever play the game, regardless of skin color. He routinely exhibited grace under pressure and changed the way black athletes were perceived in America. The same could be said of Arthur Ashe. Both men exhibited a high level of integrity and broke down many barriers for African Americans in their respective sports.

Like golf, tennis has four tournaments that are considered Grand Slam Events. Winning one of these events is enough to immortalize any player. In 1968, Arthur won the U.S. Open while he was still an amateur, becoming the first black male to ever win the U.S. Open. In 1970, he won the Australian Open, again becoming the first African American to win this major. Five years later he won the most prized award in tennis, the Wimbledon championship. Arthur did not win the singles title at the French Open, the fourth grand slam event, but he did win the doubles championship. In his 10 years as a pro, Arthur won 51 tournaments, including 33 singles titles and 18 doubles titles. By anybody’s account, Arthur was a tremendous tennis player, and as such, was inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame.

Once Arthur became a prominent athlete, he used his status to become a social activist. He later reflected, “I wanted to make a difference, however small, in the world, and I wanted to do so in a useful and honorable way.” After Arthur won the U.S. Open in 1968, a white South African player told him that he would not be allowed to play in an upcoming tournament in Johannesburg. South Africa at the time was operating under the rule of apartheid, which legalized racial discrimination by the white English/Dutch colonialists against the black Africans. This ruling was reminiscent of Arthur’s younger days in Virginia, and he was not about to let this form of discrimination continue without a fight. When Arthur applied for a visa to enter South Africa in 1969, his application was rejected. He applied again in 1970, 1971, and 1972. Rejected, rejected, rejected. Finally, his application to enter the country and play in the South African Open was accepted in 1973.

Arthur played well in his matches, winning the doubles championship and finishing second in the singles event. However, Arthur’s real goal was to learn more about apartheid and create change. Before agreeing to play, he demanded that seating for his matches be integrated, a request that was granted. Before and after his matches, he went out to meet with the people and see for himself the injustices that were occurring in South Africa. Black people were not allowed to vote in their own country; whites and blacks were not allowed to marry each other; blacks were assigned to limited regions of the country.

Armed with firsthand knowledge of this oppressive government and seeing the effects it had on 19 million blacks in South Africa, he felt an obligation to do more. Arthur participated in peaceful protests against apartheid, once even getting arrested during a demonstration in Washington, D.C. He also played a major role in getting South Africa banned from Davis Cup play. He became so involved in protesting apartheid that many people said it interfered with his tennis game. In fact, Arthur only won one Grand Slam Event after 1970. However, he admitted that he was more concerned with freeing millions of oppressed people than simply winning a tennis match, saying, “We must forget ourselves and work for others, even if what we do today may or may not bear fruit until two or three generations.” Arthur Ashe understood that his role as a human being was to help others, not to serve his own self-interest.

Fortunately, the efforts of Arthur and others did not take two or three generations to create change. Frank Deford, a writer for Sports Illustrated, credited Arthur with helping to end apartheid, saying, “Arthur cracked the curtain of apartheid. Once the curtain was opened just a little bit, there wasn’t any way the South Africans could bring it back again.” In 1977, the United Nations began to put pressure on South Africa to end apartheid. The UN’s embargos, sanctions, and boycotts took their toll on the South African government, culminating in an all-race election in 1994. The winner was Nelson Mandela, a black man who had been imprisoned from 1962-1990 for opposing apartheid and the South African government.

In 1979 Arthur suffered a heart attack and subsequently underwent quadruple bypass surgery, which ultimately led to his retirement from professional tennis in 1980. In 1983 he had another heart attack and underwent double bypass surgery. In 1988 he underwent brain surgery. At that time, tests revealed the biggest blow yet to his health. Arthur was HIV-positive. He also suffered from a rare infection of the brain called toxoplasmosis, one of the two dozen or so diseases associated with HIV. In other words, Arthur had AIDS. He learned all of this information within a span of 24 hours.

At that time, being diagnosed with AIDS was a certain death sentence. Because Arthur did not use intravenous drugs, was not gay, and had been faithful to his wife, doctors were able to trace the origins of the virus to a blood transfusion that he received after his 1983 bypass surgery. At that time, blood was not tested for HIV, and Arthur became part of the two percent of AIDS patients who contracted the disease through a blood transfusion. In 1985 the U.S. government began testing all blood banks for HIV – a few years too late for Arthur.

In 1992 Arthur held a news conference to tell the world that he had AIDS. At the time of the press conference, he had less than one year to live. However, many would argue that Arthur is better known for what he did in the last 10 months of his life than what he did in the previous 49 years. Arthur soon founded the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS. Like a true champion, he was not just out to do battle with the disease, he wanted the foundation to conquer AIDS. He once said, “Maybe there’s not a cure for AIDS in time for me, but certainly for everyone else, and that should be enough to maintain this hope.”

Arthur wanted Americans to have a better understanding of the ways the disease was spread and to be more tolerant of those who had the disease. It was a time when people were afraid to shake hands with or breathe the same air as somebody with AIDS because of the unfounded fear that it was some kind of germ that could be passed from person to person. Arthur was one of the first people to dispel some of these misconceptions. He said, “You can kiss me, you can hug me, you can shake my hand, you can drink out of the same glass. I can sneeze on you, I can cough on you, you’re not going to get it from me.” Unfortunately, Arthur lost his personal struggle with AIDS, dying in 1993.

In the last year of his life he wrote his autobiography entitled Days of Grace. The following are some of the last words he ever wrote: “Whatever happens, I know that I am not going to be alone at the end. I have invested in friendship all my life. I have been patient and attentive, forgiving and considerate, even with some people who probably did not deserve it. I made the investment of time and energy, and now the dividends are being returned to me in kindness.” He knew that the more you give, the more you receive. Never was this truer than for Arthur Ashe.

Some people believe that no modern athlete since Arthur Ashe has stepped up to make such enormous contributions to humankind. As sociologist Harry Edwards said, “There’s a tremendous deficit in the dialogue around American sport as a consequence of Arthur not being here. Nobody has really replaced him. That bridge is out, it’s gone.” Even Arthur’s widow is afraid that his legacy might get lost in this era of big money and instant gratification. She reminds us, “Arthur used his life to move us all forward. The young people today don’t really know Arthur. I think it would be just an absolute travesty if they only thought of him as a tennis player who died of AIDS.” After reading this chapter, I hope you know much more than that about the great Arthur Ashe.

Check out the Student Athlete ProgramArthur Ashe is one of the 144 “Wednesday Role Models” featured in the Student Athlete Program. This program is designed to improve the character, leadership and sportsmanship of high school athletes. To learn more about this program and how you can implement it in your school: