“There is no doubt that the most important African American in our history was Martin Luther King, Jr. Similarly, there is no doubt that the second most important, and not second by much, was Jackie Robinson.”

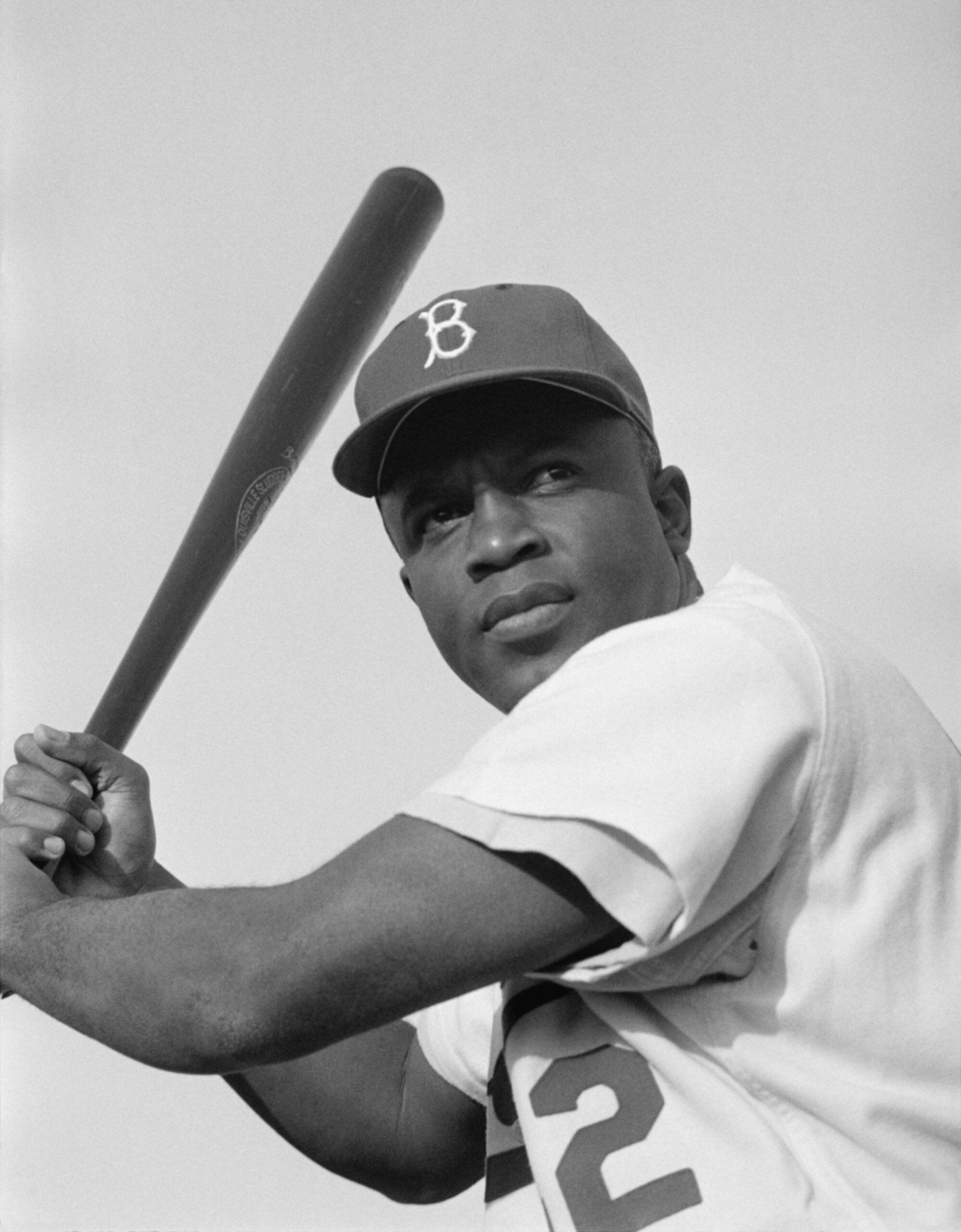

Major League Baseball began in 1876. As of the 2022 season, 20,038 individuals have played at the highest level of professional baseball. Various franchises in baseball have honored 204 of those individuals by retiring their jersey. When a jersey is retired, no player on that team can ever wear that number. However, in the history of baseball, only one person’s jersey has been retired by the entire league, meaning no player on any team can ever wear that jersey again. That individual is Jackie Robinson, the man who broke the color barrier in baseball and inspired a nation to change.

Major League Baseball began in 1876. As of the 2022 season, 20,038 individuals have played at the highest level of professional baseball. Various franchises in baseball have honored 204 of those individuals by retiring their jersey. When a jersey is retired, no player on that team can ever wear that number. However, in the history of baseball, only one person’s jersey has been retired by the entire league, meaning no player on any team can ever wear that jersey again. That individual is Jackie Robinson, the man who broke the color barrier in baseball and inspired a nation to change.

It should be noted that when Jackie played in his first major league baseball game on April 15, 1947, it was almost a decade before Martin Luther King Jr. would lead the Civil Rights movement. Prior to the 1960s, when major Civil Rights legislation was enacted, racism affected every aspect of American society, particularly in the “Jim Crow” South where segregation was the established norm. So, baseball, “America’s pastime,” was no exception. For example, in 1945, even though most of the 16 major league baseball teams resided in the north, the owners of those teams voted 15-1 to retain their “whites-only” policy.

Nevertheless, there was one owner who voted to sign black players. That was Branch Rickey. He was the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers and a fair-minded man who believed that blacks and whites should be treated equally. He also believed that players in the Negro baseball leagues could help his team win more games. So, in the summer of 1945, he quietly sent a top executive to scout the various Negro leagues to find a Black player who (a) had the ability to compete at the highest level and who (b) had the temperament to withstand the onslaught of abuse that would surely come his way.

Many were surprised that the Dodgers selected Jackie Robinson to be the first Black player to break the color line. For starters, 1945 was Jackie’s rookie year in the Negro baseball leagues, but he had yet to establish himself as a dominant player for his Kansas City Monarchs. Historians will clearly note that more accomplished Negro league ball players — for example, Josh Gibson or Satchel Paige — were more qualified than Jackie. Furthermore, although there was no doubt that Jackie had been a talented college athlete — he lettered in four sports at UCLA, starred at half back on the football team, and won the NCAA Track and Field Championship in the long jump — he was only so-so in college baseball. For example, his batting average for UCLA was a paltry .097.

Another reason that some were surprised that Jackie was selected was his temperament. The Jackie Robinson story has been told so many times that his contemporary image is that of an even-tempered and amiable individual. However, the reality is that Jackie was very assertive and frequently stood up for his civil rights as a Black man. William Forrest Sherrod, a prominent reporter of the day, made it clear. “Robinson was not a pacifist. He had a temper and an amazing vocabulary of four-letter words.” Moreover, Jackie openly acknowledged that his weakness in life was his temper and that he had made a habit of standing up for himself. For example, after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, Jackie was drafted into the US Army and commissioned as a lieutenant. When stationed in Texas, he was asked to move to the back of a bus, which was expected of Black people in the South. When he refused, he was court-martialed. Although Jackie later was acquitted by an all-white panel of nine officers, these proceedings kept him from serving with his unit during World War II.

After being honorably discharged in 1944, Jackie joined the Negro National League for the 1945 season. It was then, as the season came to an end, that he was asked to attend the fateful meeting with Branch Rickey, the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The meeting lasted three hours because Mr. Rickey wanted to see how Jackie would hold up under pressure. Mr. Rickey played the role of the racist and hurled all kinds of racial epitaphs in Jackie’s direction. He asked Jackie point blank, “If someone slaps you across the face and calls you a ‘so and so,’ what would you do?” Jackie responded with a question of his own: “Do you want someone without the courage to fight back?” Mr. Rickey retorted, “No, I want someone who has the courage not to fight back.” Mr. Rickey knew that fighting back would be futile because the public would always blame the retaliating Black man over the racist white man. By the end of the afternoon, the two men had reached an agreement: Jackie committed to “turning the other cheek” and let his abilities on the baseball field do the talking.

After being honorably discharged in 1944, Jackie joined the Negro National League for the 1945 season. It was then, as the season came to an end, that he was asked to attend the fateful meeting with Branch Rickey, the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The meeting lasted three hours because Mr. Rickey wanted to see how Jackie would hold up under pressure. Mr. Rickey played the role of the racist and hurled all kinds of racial epitaphs in Jackie’s direction. He asked Jackie point blank, “If someone slaps you across the face and calls you a ‘so and so,’ what would you do?” Jackie responded with a question of his own: “Do you want someone without the courage to fight back?” Mr. Rickey retorted, “No, I want someone who has the courage not to fight back.” Mr. Rickey knew that fighting back would be futile because the public would always blame the retaliating Black man over the racist white man. By the end of the afternoon, the two men had reached an agreement: Jackie committed to “turning the other cheek” and let his abilities on the baseball field do the talking.

When Jackie reported to the Dodgers’ minor league affiliate in the spring of 1946, he fully understood that he would need all the composure his body could muster. Many Americans were not happy to see a Black man suit up to play the game they loved against white men. Half of his teammates initially wouldn’t speak to him or shake his hand. Fans threw black cats and watermelons on the field. Pitchers deliberately threw fastballs at his head, and base runners purposefully slid into him. He was called every derogatory name imaginable: “Nigger, go back home;” “Baboon, go back to the jungle;” “Shine my shoes, shoe-shine boy.”

Mr. Rickey often visited the minor league club to watch him play. One time after a spectacular play by Jackie, he turned to Clay Hopper, the manager of the team and enthusiastically said, “That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen a human being do.” Hopper responded, “Mr. Rickey, do you really believe they’re human?”

Through it all, Jackie kept his cool. Everyone knew he could hear every cruel word, but he did his best to ignore it all. Civil rights leader Jesse Jackson recalled, “In the face of such hostility and such meanness and violence, he did it with such amazing dignity.” Jackie let the game of baseball become the great equalizer. He led the league with a .349 batting average and a .985 fielding percentage. At the end of the season, he was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player — by a group of white sports writers.

Jackie reported back to the minor league team the following spring. Only, this time, he was told to switch his fielding position from second base to first base. Jackie was puzzled by this because he had never played first base. However, the reason soon became clear. Two days before the start of the season, Jackie was called up to the Brooklyn Dodgers to start at first base. History was made on April 15, 1947, when Jackie played his first major league baseball game in front of 26,623 fans. The late US Congressman John Lewis put this moment in its proper context:

“Jackie gave the Black community a sense of hope, a sense of pride, and if this young Black man can succeed, we all can succeed.” In many ways, his mere presence on the field changed everything.

Of course, at the major league level the jeers grew louder, and the insults became more intense. Initially, some of Jackie’s own teammates circulated a petition around the clubhouse to ban him. Later, players from other teams discussed a strike. A filing cabinet in Mr. Rickie’s office contained hundreds of written death threats that Jackie received that first year. When the team played games in the South, Jackie could not stay in the same hotels or eat in the same restaurants as his teammates. At every game, racist fans taunted Jackie from the stands. Teammate Duke Snider later acknowledged, “I don’t know if anybody could’ve put up with what Jackie went through.”

Of course, at the major league level the jeers grew louder, and the insults became more intense. Initially, some of Jackie’s own teammates circulated a petition around the clubhouse to ban him. Later, players from other teams discussed a strike. A filing cabinet in Mr. Rickie’s office contained hundreds of written death threats that Jackie received that first year. When the team played games in the South, Jackie could not stay in the same hotels or eat in the same restaurants as his teammates. At every game, racist fans taunted Jackie from the stands. Teammate Duke Snider later acknowledged, “I don’t know if anybody could’ve put up with what Jackie went through.”

In many ways, these racist views showcased the worst side of America. However, it is important to note that many people were ready for change and actively rooted for Jackie’s success. For example, it was his minor league manager, Clay Hopper, who actually recommended that Jackie get his shot at the big leagues. It seems that after developing a personal relationship with Jackie and witnessing his character over time, the manager could no longer maintain his stereotypes of Black people. Also, when his teammates started their petition to ban Jackie, it was Dodger manager Leo Durocher who told the players where they could stick that piece of paper. Later, in no uncertain terms, Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler quickly squelched any player strikes around the league. It should also be noted that Jackie routinely played in front of packed stadiums, which meant that Jackie got to hear the cheers and the encouragement too: “The fans were treating me magnificently all around the circuit. Playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers is the best job I ever had.”

When Jackie was struggling through a 0-22 slump at the plate, teammate Pee Wee Reese, walked over to first base, put his arm around Jackie and told him, “Don’t worry about all that noise. Let’s just play ball.”

Jackie kept his composure through it all and proved himself to be a man of great character. At the same time, his actual play on the field proved that he not only belonged in the major league, but he also was one of the greatest ball players of his generation. At the end of his first season in the majors, he led the team in seven offensive categories and was named Rookie of the Year (an award that was later named in his honor). In his 10-year career, Jackie played in six world series, winning one. He was named the National League MVP in 1949 and was named to six All-Star teams. In addition to his lifetime .311 batting average, he stole base 197 times, including an astonishing 19 at home plate.

Jackie Robinson was a catalyst for long-overdue change in America. Before he retired in 1956, 51 Black players joined the major leagues, including Larry Doby who joined the Cleveland Indians just three months after Jackie joined the Dodgers. Seven of those Black men were named Rookie of the Year and six received MVP trophies. Other monumental changes occurred in American culture. For example, in 1948, just one year after Jackie’s debut, President Truman signed legislation to desegregate all aspects of the military. In the 1954 landmark Brown vs. the Board of Education case, the United States Supreme Court ruled that all schools must be integrated. The following year, Rosa Parks refused to sit in the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Within a few days of that, the auspicious public career of Martin Luther King, Jr., was launched right alongside the Civil Rights Movement.

It is unreasonable to give Jackie Robinson credit for all of these advances in American culture. But it is fair to say that he opened a lot of eyes and minds. It was impossible to see a Black man play “America’s game” with talent equal to or surpassing white players and not question all the racist policies that permeated our society. American historian George Will rightly noted: “There is no doubt that the most important African-American in our history was Martin Luther King, Jr. Similarly, there is no doubt that the second most important, and not second by much, was Jackie Robinson.”

In retirement, Jackie became a vice president of a major corporation and started a Black-owned and Black-led bank in Harlem. He remained politically active and consistently urged America to keep moving forward on race relations. In 1972, Jackie agreed to appear at a game to commemorate the 25th anniversary of his debut in the major leagues. In his final public appearance, he gave a short speech:

I’m extremely proud and pleased to be here this afternoon but must admit that I’m gonna be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third base coaching line one day and see a black face managing in baseball.

He then exited the stadium and, nine days later, he exited this world at the young age of 53. Jackie left behind a beautiful wife, adoring children, and a wonderful legacy. Since his untimely death, the honors and awards have continued to come his way. In 1999, he was named a starter for the Major League All-Century Team. Three postage stamps have been commemorated to honor his contributions to American society. He has posthumously received the Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honors for an American citizen. Not only did professional baseball retire his jersey, but they officially named April 15 Jackie Robinson Day. On this day each year, every player on every team wears number 42 to honor this great man. Perhaps sports commentator Bob Costas best articulated Jackie’s life and contributions when he asked: “Were there better baseball players than Jackie Robinson? Yes. Were there more important baseball players than Jackie Robinson? Who?”

Discussion Questions

- Of all the great black baseball players in the “Negro” Leagues, why do you think Brooklyn Dodgers team owner selected Jackie Robinson to be the first black player to play in the major league?

- List all the sports that Jackie played in high school and college.

- Describe the unfair treatment that Jackie received in the minor leagues and the major leagues.

- How did Jackie respond to these racial attacks on him? Do you think you could possess that type of composure?

- What inspires you about Jackie’s life and how can his example make you a better person?

If you wait long enough that good things will start to appear.

ghhgfhhgvb