On July 4, 1776, representatives from the original 13 colonies signed the Declaration of Independence, which laid the foundation for freedom and democracy in what would become the United States of America. The second paragraph of this document clearly states the beliefs of our founding fathers, “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

Unfortunately, at the time, these rights only pertained to white men. Slavery was the law of the land, meaning that black people were owned and treated like property. They were viewed as an inferior and uncivilized race and were not granted any of the rights promised in the Declaration of Independence. Slavery began to disappear in the northern states during the early 1800s, but it would require the Civil War (1860–1864) and the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 for slaves to be freed in the American South.

While the Civil War ended an ugly chapter in American history, the era of segregation and Jim Crow laws was just beginning. The Civil War freed blacks from slavery, but gaining equal rights took many more decades. For roughly the next 100 years, blacks and whites living in the South had “separate but equal” facilities in public places. Signs saying “White” or “Colored” designated separate drinking fountains, restrooms, barbershops, movie theaters, and other public facilities. This precedent was affirmed in 1896 in Plessy v. Ferguson, when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a decision finding Homer Plessy guilty of sitting in the whites-only section of a train in Louisiana. Segregation was snobbery in its ugliest form because it was founded on the misguided premise that whites were the superior race, and blacks were not good enough to sit, be educated, or eat with whites. This separation of the races was a constant reminder that everyone had a place in society and blacks were at the bottom. Separate was not accompanied by equal.

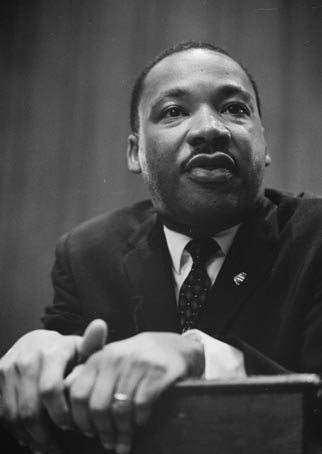

By the middle of the 20th century, black people refused to tolerate this continued attack on their dignity and self-respect. Black individuals had always fought racism in various ways with differing degrees of intensity, but beginning in the 1950s and 1960s they spoke up collectively to fight for equality. This unified voice had a name—the Civil Rights Movement. The leader behind that unified voice was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. His greatest contribution was recruiting thousands of mostly black individuals to join his nonviolent army and to use the highly effective tactics of sit-ins, marches, and boycotts to gain equality. As a result, civil rights protestors made America a better country for all of its citizens. From the moment he came into the national spotlight in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1954 to the day he was assassinated in 1968, King’s strong spirit and charismatic leadership inspired a generation of people to fight for their unalienable rights—the same rights that were guaranteed to all people in the Declaration of Independence.

When Martin Luther King Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, there was no immediate indication that he would change the world. His given name was Michael. When he turned five, his father, also named Michael, changed his own name to Martin Luther, after the founder of the Protestant religion. Young Michael followed suit and thus became known as Martin Luther King Jr. With such a name, it seems he was destined for greatness. His father was pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, and his mother, Alberta Williams King, stayed home to care for their three children. They were inspiring role models for their son. “I have a marvelous mother and father,” King once wrote. “I can hardly remember a time that they ever argued or had any great falling out.”

King deeply admired his father, saying, “He is a man of real integrity, deeply committed to moral and ethical principles.” As a community leader, Martin Luther King Sr. championed the rights of blacks, working diligently to register black voters and to help black teachers earn the same salary as white teachers. One day a policeman pulled him over for a minor traffic infraction and referred to him as “boy”—one of many demeaning terms white people directed at blacks during that time. Mr. King calmly pointed to his son and said, “That’s a boy there. I’m a man.” On another occasion, father and son waited patiently at a store to buy shoes. The clerk insisted that they move to the “colored” section of the store before he would agree to assist them. Mr. King said, “We’ll either buy shoes sitting here or we won’t buy shoes at all.” When the clerk refused, King took his son and left the store. Young Martin was learning the ways of the segregated South. He also learned to emulate his father’s method of confronting racism with dignity and self-control.

King deeply admired his father, saying, “He is a man of real integrity, deeply committed to moral and ethical principles.” As a community leader, Martin Luther King Sr. championed the rights of blacks, working diligently to register black voters and to help black teachers earn the same salary as white teachers. One day a policeman pulled him over for a minor traffic infraction and referred to him as “boy”—one of many demeaning terms white people directed at blacks during that time. Mr. King calmly pointed to his son and said, “That’s a boy there. I’m a man.” On another occasion, father and son waited patiently at a store to buy shoes. The clerk insisted that they move to the “colored” section of the store before he would agree to assist them. Mr. King said, “We’ll either buy shoes sitting here or we won’t buy shoes at all.” When the clerk refused, King took his son and left the store. Young Martin was learning the ways of the segregated South. He also learned to emulate his father’s method of confronting racism with dignity and self-control.

Unfortunately, growing up in the South, Martin had many hard lessons yet to learn. Early in his life, Martin’s best friend was a white boy. They often played together when they were very young, but because of segregation they enrolled in separate schools. Soon the neighbor boy told Martin that they could no longer spend time together. Like countless other black mothers of the time, Mrs. King reluctantly sat her son down and explained the concepts of discrimination, prejudice, and segregation. She told him that many white people would perceive him as inferior. More importantly, she ended this talk with a statement she never wanted him to forget: “You are as good as anyone.”

In many ways Martin had a normal childhood. He played baseball and football. He loved reading and discovered several black role models through books. Martin was very bright. He skipped several grades in elementary school and was admitted to Booker T. Washington High School, which was named for one of his role models. When he was 14, one of his teachers entered him in an educational competition. His speech, “The Negro and the Constitution,” won first place. On the way home from the competition, however, he and his teacher sat in the “colored” section of the bus. As the bus filled up, the driver instructed them to give up their seats to a white person. When they didn’t move fast enough to suit him, the driver began cursing at them. Martin was forced to bite his tongue, but later recounted, “That night will never leave my memory. It was the angriest I have ever been in my life.” As similar experiences accumulated over the years, his contempt toward white people grew.

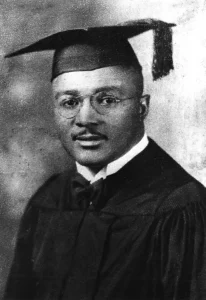

Martin was accepted to Morehouse College, an all-black school in Atlanta, at the age of 15. Even at this tender age, he knew he wanted to dedicate his life to helping others. To earn money for college, he harvested tobacco in Connecticut. During those summers in the North, he was free from Jim Crow laws and enjoyed freedoms he was denied in his hometown of Atlanta. He went to fine restaurants, sat wherever he pleased, and was treated with respect. However, as soon as the train passed Washington, D.C., he was sent back to the “colored” section. After having a taste of what life could be like without segregation, he had trouble adjusting to the loss of freedom, saying, “It did something to my sense of dignity and self-respect.” Partly due to the influence of his father and two of his mentors at college, King decided to enter the ministry. He also understood the powerful influence preachers had in the black community. He was ordained as a minister at the age of 18 and graduated from Morehouse College the next year. He then enrolled at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania. After graduating at the top of his class, he entered Boston University to earn a doctoral degree.

College was an enlightening experience for Martin. It changed the way he viewed the world. He began to interact with white people who empathized with his struggle to overcome racism and shared his desire to end segregation in the South. “As I got to see more of white people…my anger softened,” he said. “I began to see that they weren’t the enemy. The enemy was segregation itself.” Martin also began to encounter philosophers and ideas that influenced his thinking and began shaping him as the future leader of the civil rights movement. He read the work of Henry David Thoreau, who coined the term “civil disobedience.” Thoreau wrote, “If a law is unjust, men should refuse to cooperate with it. They should be willing to go to jail for not obeying such a law.” He was also heavily influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, who used nonviolent resistance to free India from oppressive British rule. “It was in this Gandhian emphasis on love and nonviolence that I discovered the method for social reform that I had been seeking,” he said. He believed that he could help his race overcome racism and segregation by combining Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance with Jesus Christ’s principles of love and forgiveness.

Martin Luther King Jr. seemed ready for greatness. His parents gave him a solid moral foundation and his education provided him with a remarkable ability to think and reason. He was spiritually grounded and exhibited a calm demeanor, which gave him confidence, even in difficult situations. He had a rare ability to lead people with his actions and inspire them with his words. The final ingredient was added when he married Coretta Scott. King said he knew he wanted to marry her after less than an hour of meaningful conversation. He claimed that she had all the qualities he was looking for in a wife: “character, intelligence, personality, and beauty.” They were married in June 1953. King later credited his wife for sustaining him through the tough times that would soon come. “I am convinced that if I had not had a wife with the fortitude, strength, and calmness of Corrie, I could not have withstood the ordeals and tensions surrounding the movement,” he said.

After graduating from Boston University, King had several job offers, most of which were in the Northeast. However, he and his wife felt a “moral obligation” to return to the South and try to change the plight of blacks there. King accepted an offer to become minister of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Montgomery was often considered the heart of the South because it was the most segregated city. From his church, King could actually see the spot where Jefferson Davis took his oath as the President of the Confederate States. Although the Civil War had been over for 90 years, Confederate flags remained clearly visible and the sounds of Dixie could be heard from his church. If King wanted to change things, he had certainly come to the right place.

Not only was it the right place, it was also the right time. In  1954 the Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board of Education, declaring that segregated schools were unconstitutional. This decision essentially reversed the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 and set in motion the wheels of change. On December 1, 1955, a 42-year-old black woman named Rosa Parks further challenged the chokehold of segregation by refusing to give up her seat on a city bus. In Montgomery, blacks were expected to sit in the back of the bus and whites sat in the front. On her way home from work one day, Parks sat in the middle—the unreserved section. As the bus filled up with white people, the bus driver directed her to give up her seat for them. When she calmly said, “No,” she was arrested for violating segregation laws.

1954 the Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board of Education, declaring that segregated schools were unconstitutional. This decision essentially reversed the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 and set in motion the wheels of change. On December 1, 1955, a 42-year-old black woman named Rosa Parks further challenged the chokehold of segregation by refusing to give up her seat on a city bus. In Montgomery, blacks were expected to sit in the back of the bus and whites sat in the front. On her way home from work one day, Parks sat in the middle—the unreserved section. As the bus filled up with white people, the bus driver directed her to give up her seat for them. When she calmly said, “No,” she was arrested for violating segregation laws.

The following morning King received a phone call from E.D. Nixon, who had just posted bond for Rosa Parks and exclaimed, “We have taken this type of thing too long already.” Less than 12 hours later, more than 40 ministers and civic leaders gathered for a meeting at King’s church. The leaders unanimously decided to organize a boycott of the city buses. They handed out thousands of flyers and passed the word through black churches. The following Monday, December 5, the black community responded to the challenge. One empty bus after another passed King’s house that morning. Thousands of black individuals walked to and from work, sometimes up to 10 miles. King said, “As I watched them, I knew that there is nothing more majestic than the determined courage of individuals willing to suffer and sacrifice for their freedom and dignity.”

The boycott was successful, but to have any long-term impact, black citizens knew they needed to organize a long-term effort. The same 40 leaders who organized the initial boycott met again later that day. They formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and elected 26-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. as their leader. He was surprised to be chosen, because of his age and the fact that he had only been a resident of Montgomery for just over a year. Nonetheless, he was pleased to accept the leadership position. Later that night, the MIA held an open rally. An estimated 5,000 people crowded the church and surrounding streets. King did not disappoint the masses. With only 15 minutes of preparation and without the use of notes, he gave one of the most inspiring speeches of his life.

You know, my friends, there comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression…. We are not wrong. We are not wrong in what we are doing. If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God almighty is wrong…. We are going to work together. Right here in Montgomery, when the history books are written in the future, somebody will have to say, “There lived a race of people, a black people…who had the moral courage to stand up for their rights. And thereby they injected a new meaning into the veins of history and civilization.”

That night the world was introduced to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. through radio and television. And that night the black community unanimously decided to continue their boycott of city transportation until three demands were met: bus drivers would begin treating black passengers with courtesy; passengers would be seated on a first-come, first-served basis; and black bus drivers would be employed on predominantly black routes. For the next 382 days—whether the weather was hot and muggy or cold and rainy—black people refused to ride the city buses.

King viewed the boycott as a nonviolent protest against unjust laws. Years later he wrote in his autobiography, “…What we were really doing was withdrawing our cooperation from an evil system.” Of course, many of the white people in Montgomery, including city and state government officials, did not see it that way. They tried everything imaginable to end the boycott and resist changing segregation laws. As King would explain later, “… no one gives up his privileges without strong resistance.”

Much of the anger of the city’s white leaders was directed at King himself. He was arrested for driving 30 miles per hour in a 25-mile-per-hour zone, the first of 30 times he was arrested during the fight for equality. He received up to 40 threatening phone calls per day. One such caller said, “Listen, nigger, we’ve taken all we want from you; before next week you’ll be sorry you ever came to Montgomery.” A few nights later, his house was bombed. His wife and first born daughter were in the house at the time, but both survived. Hundreds of black individuals began to form an angry mob outside his house. King kept his composure and addressed the crowd with the following words:

We believe in law and order. Don’t get panicky…. Don’t get your weapons…. We are not advocating violence. We want to love our enemies. I want you to love our enemies. Be good to them. Love them and let them know you love them…. What we are doing is just.

In the end, his message of self-control won out. On November 13, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that Alabama’s law requiring segregation on buses was unconstitutional. When the order to end this discriminatory policy finally reached Montgomery, the MIA officially ended the protest. King and several of his closest associates were the first blacks to get back on a bus. In a moment that was caught by television cameras and microphones, the bus driver greeted them with a warm smile and said, “We are glad to have you this morning.” In a symbolic gesture, King promptly sat down in the front row next to Glen Smiley, a white minister.

In the end, his message of self-control won out. On November 13, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that Alabama’s law requiring segregation on buses was unconstitutional. When the order to end this discriminatory policy finally reached Montgomery, the MIA officially ended the protest. King and several of his closest associates were the first blacks to get back on a bus. In a moment that was caught by television cameras and microphones, the bus driver greeted them with a warm smile and said, “We are glad to have you this morning.” In a symbolic gesture, King promptly sat down in the front row next to Glen Smiley, a white minister.

The boycott was not just about sitting in the front of the bus; it was about access, equality, and respect. After the boycott ended, King noted the following difference, “The Montgomery Negro had acquired a new sense of somebodiness and self-respect, and had a new determination to achieve freedom and human dignity no matter what the cost.” One black janitor also noted the change. “We got our head up now and we won’t ever bow down again.”

After achieving success in Montgomery, King and his associates formed a church-based organization composed of black ministers from Southern states. King was elected to serve as chairman of the new organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). He and his family soon moved to Atlanta to better organize the civil rights movement. As chairman of SCLC, he was responsible for giving speeches across the country and inspiring social change. He was convinced that nonviolent resistance, which included sit-ins, boycotts, and marches, could be a vehicle for change. If it had worked in Montgomery, he thought, it could end segregation everywhere. All it took was courage, cooperation, and the ability to maintain composure in the face of adversity.

Similar sit-ins soon followed in more than 100 cities. Young people, mostly college students calling themselves Freedom Riders, boarded buses in Washington, D.C., and traveled throughout the South. Their main objective was to stop in select cities and use segregated facilities—whites would use “colored” restrooms and blacks would drink from “white” drinking fountains.

Although these began as peaceful demonstrations, they did not always stay that way. The Freedom Riders were routinely beaten with chains, baseball bats, and pipes. When white Southerners heard Freedom Riders were coming to their cities, they showed up in droves. Governor John Patterson of Alabama warned the Freedom Riders to stay out of his state, saying, “Blood’s going to flow in the streets.”

Other violent incidents were happening with more frequency. Members of the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi murdered 14-year- old Emmitt Till after he allegedly whistled at a white woman. Medgar Evers, a high-ranking member of the NAACP, was shot and killed outside his house in the same state. Four little girls were killed when a bomb exploded at a black church in Alabama. Members of the 101st Airborne Division were called in to supervise the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Another 20,000 troops were needed at the University of Mississippi when hundreds of white individuals took up arms to deny James Meredith, a black man, entrance to the university.

King was not directly involved in most of these demonstrations. However, he was the glue that kept the movement together. When emotions reached the boiling point, he had the ability to calm the waters. He knew that blacks had the moral high ground and consistently delivered his message of self-control. Nonviolent resistance came from a position of strength, and this strategy enabled the civil rights movement to reach its noble objectives in a just manner. Thousands of people were recruited into King’s nonviolent army under the condition that they would not respond to violence with violence. “You must be willing to suffer the anger of the opponent, and yet not return anger,” King would say over and over. “You must not become bitter. No matter how emotional your opponents are, you must be calm.” It was a hard pill to swallow for many blacks who had dealt with racism all their lives, but by using the strategy of nonviolent resistance, they were making tremendous strides in their quest for equality. The civil rights movement was becoming so successful that King declared, “Old man segregation is on its deathbed.”

King was not directly involved in most of these demonstrations. However, he was the glue that kept the movement together. When emotions reached the boiling point, he had the ability to calm the waters. He knew that blacks had the moral high ground and consistently delivered his message of self-control. Nonviolent resistance came from a position of strength, and this strategy enabled the civil rights movement to reach its noble objectives in a just manner. Thousands of people were recruited into King’s nonviolent army under the condition that they would not respond to violence with violence. “You must be willing to suffer the anger of the opponent, and yet not return anger,” King would say over and over. “You must not become bitter. No matter how emotional your opponents are, you must be calm.” It was a hard pill to swallow for many blacks who had dealt with racism all their lives, but by using the strategy of nonviolent resistance, they were making tremendous strides in their quest for equality. The civil rights movement was becoming so successful that King declared, “Old man segregation is on its deathbed.”

The only way to put segregation to bed for good was to win important battles in cities like Birmingham, Alabama. The state’s outspoken governor, George Wallace, made the following vow in his inaugural address: “Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow, Segregation forever.” His racism was only outmatched by Eugene “Bull” Connor, the commissioner of public safety in Birmingham. Together, they governed the most segregated city in America, making it a prime target of King’s nonviolent protests.

Because black people had so much buying power, protestors placed most of their emphasis on the business community. They would organize sit-ins, picket local stores, and eventually march on the city until business owners agreed to integrate lunch counters, rest rooms, fitting rooms, and drinking fountains. Hundreds of protesters were arrested every day. King decided to march down to the city courthouse himself. As expected, he was arrested and put in solitary confinement. While in jail, eight white clergy from Birmingham submitted a letter to the local newspaper criticizing the demonstrations. On scrap pieces of paper, King meticulously addressed each of their complaints in his now-famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

The civil rights crusade continued as thousands of college, high school, and even elementary school students were trained in nonviolent tactics. On the first day of the Children’s Crusade, 1,000 marched on the city. On the second day, more than 2,500 followed suit. In response, Commissioner Connor ordered firefighters to shoot powerful streams of water at the children and to release German Shepherd dogs on them. On the third day, the children returned in greater numbers, even more determined to prevail. Connor turned once again to the firefighters and yelled, “Let them have it.” At that moment, the children knelt down and began to pray. Apparently mesmerized by the children’s courage, the firefighters refused to turn on the hoses. The children politely stood up and marched by them without any further attacks. Birmingham’s business leaders soon realized that the movement for equality could not be stopped. They quickly met all of the demands set forth by King. After Birmingham became integrated, it was just a matter of time before Jim Crow was dead and the walls of segregation came tumbling down.

With more confidence than ever before, King led a march on the nation’s capital in August of 1963. On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, overlooking the National Mall, he gave his famous, “I Have a Dream” speech to more than 250,000 people.

I say to you today, my friends: so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed—we hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.

King had many dreams. He not only wanted to end segregation, he wanted all people to be treated fairly and equally. He wanted people to be judged by the content of their character and not by the color of their skin. He wanted racial harmony. He wanted to eliminate poverty. At every turn, King fought for these ideals, but in the end his dreams were cut short. In an eerie way, it seemed like he knew before his assassination that he was about to be killed. In his final speech, he said:

I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And so I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man.

On the following day, April 4, 1968, King met with his staff to discuss a march that was to be held in Memphis, Tennessee. While on the balcony of his motel, he was shot with a high- powered rifle fired from across the street. The assassin was an escaped convict named James Earl Ray. Dead at the age of 39, King left behind a wife and four young children. His best friend, the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, conducted the funeral service. Afterward, 50,000 mourners joined the precession to the cemetery. Etched into King’s tomb are the following words: “Free at last, free at last, Thank God Almighty, I’m free at last.”

Before he died, King said, “If one day you find me sprawled out dead, I do not want you to retaliate with a single act of violence. I urge you to continue protesting with the same dignity and discipline you have shown so far.” It would have saddened him to know that more than 100 American cities erupted into violence after his death. Millions of dollars in damages were reported and dozens of black people were killed. The National Guard, once called out to protect black people integrating Southern cities, was now protecting cities from their wrath. But that violence is not King’s legacy.

Martin Luther King Jr. was honored many times during his lifetime. In 1963 he became the first black person to be named Time’s Man of the Year. The following year, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. At the age of 35, he was the youngest person ever to win this prestigious award. 15 years after King’s death, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill declaring January 15 as a national holiday memorializing Martin Luther King Jr. He is the only American to have a national holiday named exclusively for him.

Now, every year millions of Americans of all races can reflect on King’s powerful message of tolerance, equality, and justice. His legacy reminds us what can be accomplished if we work together to overcome our differences. The ability to keep his composure in the face of anger, violence, and hatred is the single greatest factor that enabled him to change so many lives. We all have a duty to continue King’s dream of freedom and equality in America. We must never forget the sacrifices he and thousands of others made to ensure all Americans might enjoy the unalienable rights guaranteed in the Declaration of Independence. And we must never take these rights for granted. Exercise your right to vote, study hard at the school of your choice, and find a way to contribute to society. Finally, we can honor King by learning to exercise self-control. There are many excuses to get angry, but no good reasons to lose your composure. When we have dignity ourselves and show respect for others, we are honoring the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Discussion Questions

- Martin Luther King Jr. combined the tenets of which three individuals as the basis of his non-violent resistance?

- What tactics did King and the MIA use to create the type of meaningful change for black people in this country?

- What role did children play in the civil rights movement?

- After a bomb exploded in King’s house with his wife and child present, how did Dr. King respond when an angry mob formed outside his house?

- What inspires you about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and how can his life make you a better person?

😘

🥰

Very good story. loved reading it.

I think that If you speak up and love a lot you can end anything bad. Even segrigation.

Pingback: Overcoming Hate with Friendship and Communication – Kevin Mauermann's WordPress Site

I think you should never give up and continue chasing your dreams <3