“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, I am the greatest, Muhammad Ali.”

It was 1954. Twelve-year-old Cassius Clay was furious. Someone had stolen his brand new red Schwinn bike near his home in Louisville, Kentucky. Cassius was hollering to anyone who would listen, “When I find the guy who took my bike, I’m gonna ‘whoop’ him.” Someone directed young Cassius to a police officer who lived in a nearby apartment. As fate would have it, this policeman, Joe Martin, also operated a boxing gym in his spare time. He told Cassius that he ought to first learn how to fight if he was going to whoop someone. This sequence of events was what led Cassius into the boxing ring. Cassius redirected his anger into one of his lifelong passions – boxing. If not for this brief encounter on the steps of Grand Avenue, the world might have never known the man who would later become Muhammad Ali.

Cassius brought his passion to the ring. He had a promising amateur career, winning 100 fights and only losing five. He won six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles and two national Golden Gloves titles. The highlight of his amateur career was winning the Light Heavyweight gold medal in the 1960 Summer Olympics. Cassius was proud to represent his country. As it turns out, parts of his country weren’t proud of him. In 1960 Louisville was still a part of the segregated south, and Cassius was refused service at a “white’s only” restaurant. According to his autobiography, after this incident Cassius threw his gold medal into the Ohio River.

Cassius never lacked for confidence. He had so much passion for boxing and life, he couldn’t keep it inside. He was outlandish. He bragged and he boasted,

“It’s hard to be humble when you’re as great as I am.” “I’m pretty.” “I’m the greatest.” He would even make up poems about his opponents and recite them in public. “I’ve wrestled with alligators. I’ve tussled with a whale. I done handcuffed lightning. And thrown thunder in jail.” Cassius also was a trash talker. “Frazier is too dumb to be champ.”

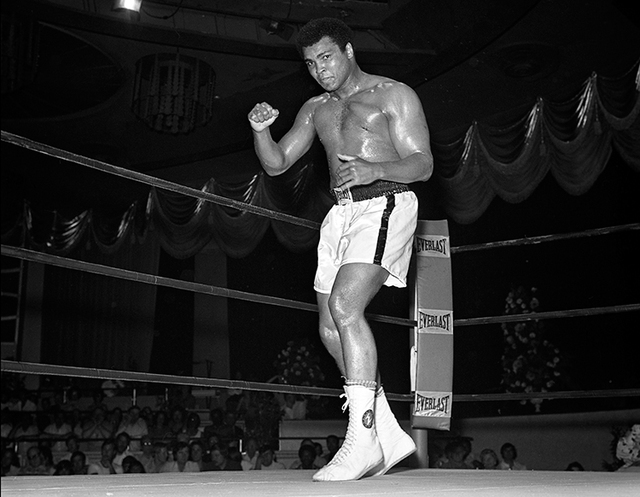

Of course, no one had ever seen someone box like him either. He constantly circled and danced in the ring. He would later call this move the “Ali Shuffle.” But he did more than dance. He had superior hand speed and lightning reflexes. Floyd Patterson, one of his opponents in the ring said, “It’s very hard to hit a moving target, and Ali moved all the time, with such grace. He never stopped.” He could also ‘take a punch’ as well as anyone. He held his hands low and he threw jabs from unconventional angles. All this style and grace added to his persona.

Cassius quickly ascended to the top, amassing a 19-0 record as a pro. In 1963, he was the number one contender in the world, ready for his shot to take on then-world heavyweight champion Sonny Liston. Cassius was a 7-1 underdog to the champ. Still, Cassius taunted Liston mercilessly before the fight, referring to him as the “big ugly bear.” Some say he won the fight at the pre-fight weigh-in. And when the fight did ensue, it was obvious that Cassius was faster, bigger, and dominant. When Liston did not answer the bell before the 7th round, Cassius became the youngest heavyweight champion ever.

Shortly after this fight, Cassius developed another one of his passions when he converted to the Muslim religion by joining the Nation of Islam. One of the leaders of this movement, Elijah Muhammad, renamed Cassius as Muhammad (one who is worthy of praise) Ali (most high praise). Much of America had difficulty accepting this dramatic change. At the time, it was unprecedented. But Ali declared “Cassius Clay is my slave name. I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me – black, confident, cocky. My name, not yours; my religion, not yours.” Muhammad Ali remained passionate about himself — what he did and what he believed. And, under his new identity, Ali defended his boxing title against several opponents from 1963-1967 and never lost a fight.

However, in 1966 Ali applied his uncompromising and passionate beliefs to yet another monumental matter. On April 28, 1967, amid America’s Vietnam conflict, Ali astonished — and infuriated — much of the nation: He refused to serve in the Army, stating that he was a conscientious objector. Ali explained his decision, “War is against the teachings of the Qur’an. Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong. Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam?”

Ali immediately paid a heavy price for his decision not to serve. He was stripped of his belts and all 50 states revoked his boxing license. Ali would not be allowed to get into the ring for the next three and a half years. These arguably would have been the best years of his boxing career. After all, Ali was 25-29 years old. The man who many voted the greatest athlete of the 20th Century was not allowed to compete in his chosen sport during his prime. Then, in 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously overturned Ali’s conviction.

When Ali returned to the ring, he was no longer the same boxer he once was. He was heavier and older, his punches were slower, and he couldn’t “dance”. Nevertheless, one thing did not change – Ali remained loyal to and passionate about his sport. Unlike many current “world champions” Ali didn’t avoid strong contenders. Instead, in what most people now call the Golden Age of heavyweight boxing, he took on all comers — champion boxers like Joe Frazier, Larry Holmes, and George Foreman. Just the names of his fights are legendary: “The Rumble in the Jungle,” The “Thrilla in Manila” and “The Fight of the Century.” Ali won the majority of these fights, ending his professional career with a 56-5 record.

Most agree that Ali hung on too long. His passion for his sport led him to accept at least two fights instead of retiring. In 1980, a young Larry Holmes pummeled a washed-up Ali. Holmes pleaded with the referee to stop the fight, stating that he didn’t want to hurt him further.

Four years later Muhammad Ali would be diagnosed with Parkinson’s Syndrome, a degenerative disease that affects speech and motor movement. Many doctors believe that the numerous blows he took to the head in his later career contributed to this diagnosis. Unhappily, Parkinson’s significantly impacted Ali’s full and passionate involvement in boxing. However, although Ali could no longer box, he invested himself in public service. He continually made public appearances for important causes and made huge financial contributions. Ali died at the age of 74 on June 3, 2016.

To be honest, the 1,500 words on this page cannot accurately capture the true spirit of Muhammad Ali. It’s difficult to pin him to just one trait – passion – because he embodied so many traits. He was a complex man. It almost seems like you either had to be alive to see him in his prime or you have to watch videos of his interviews to get a glimpse of who he really was and why America came to almost unanimously love him.

To be sure, many Americans loved Ali, and not just people of color. He represented the Common Man. He spoke for them on a variety of topics. Ali was also one of the most controversial athletes of any century. As such, he had his share of detractors. He angered some, he scared some, and he challenged most to contemplate their beliefs on race, religion, war, and athletes. Ali changed the world, not by what he did inside the ring, but by what he did outside of the ring.

Sportscaster Bryant Gumball puts things into perspective when he said, “If you had told somebody in 1968 that, in 1996, Muhammad Ali would be the most beloved individual on earth, and the mere sight of him holding an Olympic torch would bring people to tears, you would have won a lot of bets, a lot of bets.” But that’s what happened. When America hosted the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta and Ali lit the Olympic flame, I cried and so did everyone I knew. That moment was America’s way of apologizing and paying tribute to the man who changed America.

Sports Illustrated named Ali the Sportsman of the Century. A BBC poll asked people to name the Sports Personality of the Century and Ali received more votes than all the other contenders combined. Time Magazine named him one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century. In his lifetime, Ali appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated 37 times and on the cover of Time Magazine five times, the most of any athlete. He received just about every award that an American citizen can receive, including the Presidential Citizens Award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Arthur Ashe Courage Award.

Many will choose to remember Muhammad Ali in their own way. For me, I choose to remember him for the passion that he brought to every aspect of his life. Maybe after reading this, you will too.

Check out the Student Athlete ProgramMuhammad Ali is one of the 144 “Wednesday Role Models” featured in the Student Athlete Program. This program is designed to improve the character, leadership and sportsmanship of high school athletes. To learn more about this program and how you can implement it in your school: